From the very beginning of our lives we learn how to negotiate the spaces we live in, constructing ideas around the negotiations we make. We learn through trial, error and placement the rules of our culture, maximizing our potential within a landscape. We prioritize and negotiate our prefabricated versions of new experience with the spaces of old in our memory. Painting becomes a way of learning about the histories embedded in the ground, buildings, landscapes, and thus people.

This exhibition features ten women painters and their work pivoting our understanding of the American landscape. Each painter embodies the tradition of negotiating space and translating lived experience into abstract painted form. The title “The Shaping of America: A Painter’s Perspective” is taken from a book written by D.W. Meinig, an American Geographer. Meinig suggests the idea of “landscape” only taking on meaning in relationship and context to what is in the head of the viewer. The paintings in this exhibition suggests that the idea of landscape expands exponentially when the meaning and context of the artist are also considered. The nine women artists and their work illustrate that landscapes cannot be interpreted without considering the connections artists have to memory, experience, and ownership. By doing so, the viewer has the opportunity to see and experience the full picture.

SHAPING OF AMERICA: MEDIUM-SPECIFICITY AS PASSIVE-AGGRESSIVE RESISTANCE, 2020

—Vittori Colaizzi, Professor of Art History & author of Robert Ryman: critical texts

Although endless contention over what laws, procedures, and principles define this nation forms part of the American blueprint, Carrie Patterson and the other artists in this exhibition cannot have known the nature and extent of the cataclysms that would entangle us when they embarked on this project. Nevertheless, this exhibition of painters that boasts divergent processes and idiosyncratic connections to nature has become more urgently relevant, not less, in the face of threats to justice and civil society brought about by unbridled capitalism, white supremacy, and the state-sanctioned terror of police brutality, all in the midst of a pandemic that disproportionately affects the poor and people of color. Since I was asked to contribute an essay to this exhibition, the condition of crisis in America has compounded. Questions about what counts as American are integral to political debates, which often center on entitlement to legal protections. These abstract concepts have played out in concrete terms at the border, in legislative and judicial chambers, in hospitals, and most recently in the streets, as every thoughtful person now evaluates her or his culpability in perpetuating a racist and classist system.

Anxiety over art’s duty or capacity to affect political change seem to be ingrained within modernism itself, as its history contains numerous examples of the drive to shed reference and achieve art-for-art’s-sake autonomy, but also to participate in worldly events. In the 1960s and 70s, some critics castigated Black abstract artists for seeming to capitulate to establishment taste when they abandoned legible iconographies, but artists such as Melvin Edwards, Felrath Hines, Alma Thomas, Jack Whitten, and many others found abstraction to emblematize and actualize the liberation so sorely needed then and now. At this late date, abstract painting is still sometimes considered conservative, but in fact no approach or medium has escaped marketability or academic reification, and so whether and how conservativism or radicality are valid measures depends on the way an artwork relates to the wider sphere of human experience. This occurs on planes other than that of picturing.

By positing the landscape as not a fixed picture but a worked-through experience according to the painter’s own painstakingly developed methods, the exhibition calls for an imaginative and thoughtful viewer who looks for something other than confirmation of one’s own demands. Shaping America: A Painter’s Perspective challenges our habit of measuring the world for division and use, and, as its unapologetic subtitle suggests, to vicariously and empathetically rehearse the varied processes of the artists who, as Patterson puts it, “translat[e] lived experience into abstract painted form. . . .” This is an endeavor that occurs within relatively traditional confines of the media, without the often effective but by no means compulsory elements of collage, assemblage, video, and installation with which some painters have augmented their practices over the last century. This is a show of, if we can use the term in a pragmatic rather than a dogmatic way, pure painters.

Medium specificity was once an appealing if abstract concept that defined a focus on those aspects that set one’s work aside from other, competing or distracting elements. The backlash against modernism and specifically the criticism of Clement Greenberg made this idea anathema or at least quaint. Its renewed, relaxed form now models commitment and analogizes the agency one can take over one’s environment.

After the poststructuralist critique of the author and feminist and postcolonial criticisms of the possessive gaze, a new subjectivity has returned that does not suppose itself to be universal, but which weaves together particularities of economics, gender, race, and locality. This subjectivity, empowered as to personal choice within this constellation of factors, is on display here, exercising its authority, not over the land or of other subjectivities, but over its own self-realization. This is especially urgent in the face of an administration that denies selfhood, citizenship and humanity to women and people of color. Therefore, the entitlement to “shape America,” by which these artists insist upon a malleable, that is to say, improvable, identity to our country, is deeply threatening to those who hold that the United States is a white Christian nation bent on dominating and eradicating difference.

Although all the paintings tend to the abstract, they vary richly. Legible representation, either of isolated entities or coherent space is present, as are vigorous gestures that contrast color, texture, direction and scale, amounting to a polemical insistence on the pictorial sufficiency of these elements. In still other works, hard-edge yet gradated facets seize the plane while expanding into fathomless depths. Together these approaches reject the notion of a singular or “normative” esthetic paradigm that would render others ancillary or irrelevant. Amid the pluralism of our era, critical and curatorial models have emerged that privilege networks of citation over artists’ decisions about incident and distinctions. The networked condition David Joselit dubs “transitive” in his 2009 essay “Painting Beside Itself” renders each painting an interchangeable node within an ensemble, present or implied, while “atemporality,” the conceit of Laura Hoptman’s 2014 survey of painting at the Museum of Modern Art, pre-empts the possibility of ambitious engagement with painting’s historical forms in favor of a chic and disaffected pastiche.1 Isabelle Graw presents an false dichotomy between “painting that repudiates its supposed essence [and] one that keeps within its allotted boundaries and has unbroken faith in itself.”2 If, according to Graw, the most interesting painters (such as, in her estimation, Martin Kippenberger and Jutta Koether) are ones who have “incorporated the demands of the critique of painting into their practices and internalized the lessons of Conceptual art and institutional critique, rejecting the notion of a purely immanent and unambiguously circumscribed painterly idiom,”3 then one cannot do one without the other; one cannot responsibly paint without distending and hybridizing one’s practice. “Painting per se,” as Merlin James put it,4 is hopelessly retrograde.

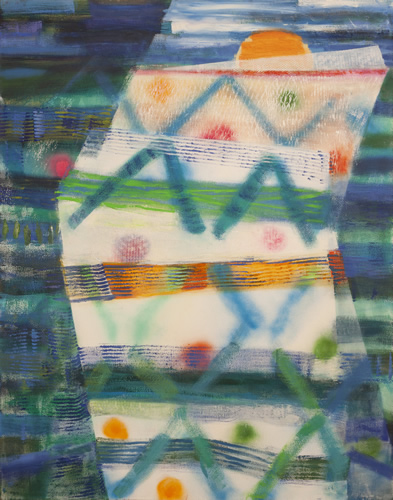

Contrary to this new orthodoxy, all of these artists propose form rather than allowing it to be determined by a matrix of visual culture. They don’t report through collage or sampling, but commit to relatively, but not absolutely traceable procedures. Each artist takes a leap between what she sees and what she does. Representation is itself a process of abstraction, wherein visual elements bleed into a productive feedback loop of perception and form-giving action. In her exhibition material, Patterson stresses the multiplicity of possibilities—each work can be “parts of a whole,” or “many places rather than one place.” In invoking Louis Dodd, Patterson points out the broad themes one may derive from specific and local subjects. Life, death, yearning, and displacement emerge not only from a sunlit wall but through a carefully placed mark or arrangement of shapes, because they are evidence of decisions.

Patterson cites the book The Shaping of America by geographer D.W. Meinig as the inspiration for this gathering of painters. In particular, she was struck by the idea that “landscape” is reconfigured according to the position and assumptions of the perceiver. Not only is this a perfect analogue for the work and experience of the painter, but it is also a license and imperative for the viewer to actively construct coherence and meaning out of that which is before her. For all their deliberate technical knowledge, these paintings are, in a way, unfinished, in that they are constellations of provocation that rely on the viewer to bring them together in her own eye and mind, to ask: What does this suggest? How could this relate to a lived experience? From what processes would this result? What effect does this part have on that? And so on. Rather than serving up a tidy and direct package that ties image and meaning into an unproblematic whole, these painters’ immersion in their crafts disconnects the terms of signification and opposes the calcification of meanings so necessary for a fascistic social order. In Patterson’s work, modular, layered colors and gestures are indicative of experiences of space and time. The gesture is measured in dialogue with geometry. She balances, or rather collides, indications of rigor and abandon, such as measured segments sometimes painted and sometimes inherently colored, which subdivide almost entropically, as well as the lavishly applied strokes, whose energy reveals on closer inspection a practiced and internalized prowess with the subtlest variations of her tools and materials. These dichotomies collapse and blend, as known categories withhold their pseudo-intellectual comfort and the viewer is left to experience, rather than evaluate.

A similar dialectic, albeit more lyrically deployed, is at work in the paintings of Cecily Kahn. Here more miniscule marks cover the surface, which intimate an architectonic yet scintillating tableau. Kahn sets up and then crosses borders with layers of color that suggest interwoven vines, dappled sunlight, and running water, but nothing so much as paint worked with care and attention.

Janis Goodman brings front and center the invention that is endemic to paintings of nature. They are always already constructions, so she asserts this quality of constructed-ness through wild caprice, always within a well-defined visual idiom. There is something nostalgic, harkening to nineteenth century romanticism with an almost sci-fi twist and not a little surrealism in her floating forms. Importantly, they show the abstraction of representation, because they are not, as a quick glance suggests, clouds, trees, nor bodies of water, but instead improvisational forms upon colored grounds that take advantage of the organic possibilities of both the medium and this realm of images.

Like Goodman, Dierdre Murphy reflects on the conventionality of representation through meticulous focus on and deliberate isolation of elements. However, unlike strategies that emerged in the 1980s that often amounted to mannered jeremiads on the supposed bankruptcy of visualization, Murphy insists on the poetic feeling inherent in her subjects through carefully considered compositions that bear an almost medieval artificiality. Her paintings’ tenuous, searching, but not quite palpable relationships between birds, flowers, abstracted lines of force, and cloud-icons amplify their potential meaningfulness, which the viewer must ultimately fullfil.

In the wake of high modernism, some critical circles clung to a linear paradigm, actually expecting photography to supersede painting as the dominant mode by which imagery and ideology would be disseminated and critiqued. Hand-in-hand with this development was to be an evolution past any regard for manual craft. As David Reed has pointed out with the lurid yet apt metaphor of the “vampire’s kiss,”5 painting has instead assimilated photography’s modes of envisioning the environment. Rather than a blanket transformation, painting often challenges these aspects of photography within its frame by means of its own tradition of embodied emotional registers.

All of this plays out in the work of Jennifer Anderson Printz, as she embraces photographic imagery of the natural environment—specifically, the sky above her home in Virginia, and deftly and selectively works over these images with graphite and paint. Her work is, in a way, a diagram of abstraction itself, as it charts her visceral but, in a conventional sense, irrational reaction to a visual stimulus. Painters will understand this perfectly: filled with aesthetic emotion, but unsatisfied by the prospect of a pictorial copy of the scene of the clouds before her, Printz follows the pull of the medium in relation to the format, expressing atmosphere, time and movement, maybe even fragrance, and in the process blurring the hackneyed categories of geometry and intuition.

The terrible hazard of categorization, whether “gestural,” “geometric,” “figurative,” “constructivist,” “surreal,” or any facile combinations, will inhibit vivid perception of these artists’ actions upon their specific works and the traditions they choose to engage. Recent exhibitions by Pat Passlof, Mildred Thompson, and Joan Thorne have shown the unending possibilities of that which has been unfairly dismissed as the exhausted idiom of gestural abstraction, which remains as individualized as a player’s touch upon an instrument. For Pamela Cardwell, a crepuscular density gives way to a pervasive but often hidden light. Vine-like tendrils painted with a medium-sized brush span considerable distance in a composition and sometimes enclose areas that are filled in with a range of mellow or searing color. Cardwell raises the contingency of form to an almost alarming pitch as near-geometric forms begin to congeal but hold back, refusing the comfort of the known. In this way the promise of midcentury abstraction remains vital, active, and tantalizingly out of reach. Kayla Mohammadi also traffics in the impalpable. Intimations of deep space co-exist with patterns that recall modernist tenets of medium specificity, with neither fealty nor bitter irony. Mohammadi instead paints an atmosphere of pleasure, one that we might again inhale or feel on our skin, even as we become acutely conscious of her paintings’ abstract constructive elements and hence their intellectual distance from, though not opposition to, sensual abandon. She paints the complex cultural inheritance of painting, to which the west is becoming ever more mindful, as well as the medium’s embedded desire for raw experience. This experience is neither promised nor owed; it simply remains a possibility. Amid her lose but rugged compositional structure, an emblematic angle or a shift in color feels as monumental as the heroic gestures and chiaroscuro of centuries past. Mohammadi makes a stand for the meaningfulness, not the symbolism, of composition itself.

Composition is also at stake in the work of Ying Li, and she draws her compositions out of the chaotic happenings of nature as well as her own generous and often oppositional marks. The tension, and indeed the drama that emerges in her work contradicts the story of modernism that culminate in minimalism, where all drama is resolved in a statement of formal wholeness. Of course, Li’s paintings more directly reference an impressionist tradition, filtered through post-war abstract gestures of both the American and European variety. It is notable that her background in both contemporary realism and traditional ink painting gives her great facility with many styles, but instead of performative virtuosity, she has selected what is arguably, if one can forgive a certain ideological inconsistency in this essay, the cutting edge in painting today, i.e., the re-direction of historical pathways thought to be closed into spectacular and ecstatic scenes that emblematize materialized thought.

Through her collaboration with scientific methods of mapping and imaging natural phenomena, Rebecca Rutstein’s paintings grasp for truth, certainty and grounded-ness. As planes, morphing grids, and more free-form painted areas proliferate, this certainty recedes, but the work is not fallacious or misguided because of this. Rather, this searching quality, present in all of these painters, is a source of sensitivity and indeed authority, because it shows a tolerance for and a visual orchestration of contradiction. Rutstein evokes digital space through her torqued and stretched grid, but the manual and intimate register, now especially valued because of its scare-ness, is also inextricably woven into her vision. We must also remember that the grid, often outlandishly elaborated, pervaded experimental drawings of the renaissance, from which perspectival studies emerged. So while Rutstein’s work therefore ruminates on the history of domination that accompanies any thorough visual plotting-out, the obfuscation that occurs functions as resistance, as mystery blots out our vision but invites vicarious touch.

Vicarious touch is also emphatically present in the work of Kendra Wadsworth, whose painting and drawing accompanies a practice in ceramics. This heightened consciousness of the material as earth-borne and earth-bound shows in her treatment of the painting-surface as a receptable for both building and excavation, wherein a kind of fantasy architecture emerges. One is invited to imaginatively inhabit the interstitial spaces created between the layers charged by her aesthetic intent, and to find there an idealized expression of creativity. The horizontal rhythms that appear are never rigid, but act as a vehicle for improvised variations, almost like a daily ritual.

The painter Marina Adams has recently compared the tenacious resolve and embrace of failure and dead ends that comprise a painter’s practice to grassroots political action such as Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter.6 Like painting, the success of these endeavors cannot be measured in news cycles, market trends, or the proceedings of academic conferences. It feels tedious and quixotic to write in defense of painting, but so is it to rage in defense of justice. I am reminded of an internet meme: “I can’t explain why you should care about other people.” Beautiful and incisive texts abound by Laurie Fendrich, Merlin James, and others that nevertheless feel written for support groups. I would like to think that each painting today is an argument, successful or not, for the specific experience it provides, and an example of the rewards of sustained attention to the constraints of a medium, including its stillness, flatness, and inescapable illusion. Encountering any one of them calls for a taking into account the subjectivity of the painter, not as a monolithic or all-consuming force, but as an additional consciousness to oneself, a challenge of otherness.

The attention for which these painters call requires a viewer who will give herself over to a mode of looking that differs from the instrumental, acquisitional, and goal-directed mindset that advanced capitalism fosters. When we don’t demand to see our own narcissistic image reflected back at us, to be re-told stories we know, but instead leap into unknown sensations, we stand a chance to break the dulling grip of administered life, from which even the Democrats won’t save us.

1 See David Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” October 130 (Fall 2009): 125–34, and Laura Hoptman, The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2014).

2 Isabelle Graw, The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium. (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018), 157.

3 Ibid, 46.

4 Merlin James, “Painting per se,” lecture transcript, Cooper Union Great Hall, New York, 28th February 2002. https://www.mummeryschnelle.com/pdf/Paintingperse.pdfAccessed June 2015.

5 David Reed in Arthur C. Danto, Isabelle Graw, Thierry de Duve, David Joselit, Yve-Alain Bois, David Reed, and Elizabeth Sussman, “The Mourning After,” Artforum v. 41, no. 1 (March 2003): 268.

6 “In the Meantime: Marina Adams. Interview by Arthur Peña.” https://salon94-site.s3.amazonaws.com/exhibitions/marina-adams-2/In-the-Meantime_Marina- Adams.pdf?mtime=20200721132002 Accessed August 2020.

The Shaping of America features the paintings of ten women artists who see and experience the genre of landscape painting in uniquely different ways. Inspired by the written word of American geographer D.W. Meinig, the exhibition highlights how each painting embodies the idea of "landscape" as experienced through the hand of the artist and the eye of the viewer. The definition of "American Landscape" will twist and turn with each layer of painted material.

“The painters in this exhibition investigate the complex relationship between humans and land through the act of painting. We all produce objects that hold our memories of spaces we once inhabited while also translating new places of emotional and psychological resonance. None of us define landscape in literal terms and we all are deeply connected to the materiality of painting that can only be felt through the body. I would encourage any viewer to look at this exhibition and the paintings contained within it through the act of visual scaffolding, through the lens of intellectual inquiry and through visceral experience. By doing so, the idea of what it means to paint an American landscape becomes tilled and can grow. ”

Participating Artists

Jennifer Anderson

Jennifer Anderson Printz is also an Associate Professor of studio art at Hollins University, where she teaches drawing, printmaking and professional practices. Her recent scholarly output includes papers given at the SGC International, College Art Association, and Southeastern College Art conferences. The Norton Simon Museum included her essay “Print University” in Proof: The Rise of Printmaking in Southern California. Anderson Printz received a MFA from the University of Georgia. She has taught and lectured at institutions across the United States including workshops at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Anderson Printz also served as president of the Los Angeles Printmaking Society and Vice President of External Affairs for SGC International.

Pamela Cardwell

Pam Cardwell grew up in Bluefield, West Virginia. She received her BFA from Virginia Commonwealth in Richmond, Virginia and her MFA from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. She lived in Turkey and taught at Bilkent University between 1998-2003. She has been awarded grants through the Joan Mitchell Foundation and in 2007 she received a Fulbright grant to research color in the frescos and manuscripts in the Republic of Georgia and Armenia. She has attended artist residencies at Yaddo, the Albers Foundation, the Millay Colony, the Edward Albee Foundation, Altos de Chavon in the Dominican Republic and Garikula in the Republic of Georgia. In 2015 she attended a residency at the Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans. Currently, she teaches as an adjunct professor at SUNY. She lives and works in Brooklyn, NY and is represented by John Davis Gallery in Hudson, NY.

Janis Goodman

Janis Goodman is a DC-based visual artist. She is a founding member of the artist cooperative group Workingman Collective. She has been the arts reviewer for the Washington PBS affiliate WETA TV, Around Town television program since 2003. Her work is in numerous American and international public collections. She has had artist residencies in Italy, the United States, Germany and England. Her work has been shown in numerous exhibitions throughout the U. S. as well as in Russia, Italy, The Netherlands, Peru, England, Japan and Germany.She is highlighted in Who’s Who in American Art, North American Women Artists of the 20th Century, the Artist Bluebook and 100 Artists of Washington, DC by F. Lennox Campello. Janis’ work has been reviewed in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Washington City Paper, and Art in America in addition to numerous other publications in American and international journals.

Cecily Kahn

Cecily Kahn is a native New Yorker who has lived in New York City most of her life. She lives and works in a large top floor loft on Canal street and Broadway, overlooking one of the busiest intersections in Manhattan. Her paintings reflect both the angularity of the city as well as the organic chaos of city life. Cecily received a BFA from Rhode Island School of Design, and went on to study printmaking in Italy for two years at the Calcographia Nazionale in Rome and the Segnio Graphica in Venice. She is represented in New York by Lohin Geduld Galery and in Atlanta by Thomas Deans Gallery. Her work has been exhibited at The National Academy, The Painting Center, Katherina Rich Perlow gallery, and Sideshow Gallery. Her work has also been exhibited at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, at the New Britain Museum of American Art, and at The Hillwood Art Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, in Bogota, Colombia. Her work has been included in the exchange shows between The Painting Center and artists groups in Ireland, Barcelona and Colombia. Her work has been reviewed in Art in America, The New York Times, The Brooklyn Rail, d'Art International, REVIEW Magazine, and in Abstract Art Online. Cecily is a current member of the American Abstract Artists group, and is Chair of the Advisory Board of The Painting Center.

Ying Li

Phyllis Koshland Professor of Fine Arts and Department Chair at Haverford College. Born in Beijing, China, graduated from Anhui Teachers University (1974-77) where she taught 1977-83. She immigrated to the United States in 1983 and received an M.F.A. from Parsons School of Design, NY in 1987. Solo exhibitions include: Centro Incontri Umani, Ascona, Switzerland; New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture (concurrent exhibition with Eve Aschheim); Lohin Geduld Gallery, NY; Elizabeth Harris Gallery, NY; The Painter Center, NY; Bowery Gallery, NY; Jaffe-Friede Gallery, Dartmouth College, NH; List Gallery, Swarthmore College, PA; Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Haverford College, PA; Gross McCleaf Gallery, Philadelphia, PA; Marie Salant Neuberger Campus Center Gallery, Bryn Mawr College, PA; Enterprise House, County Mayo, Ireland; and ISA Gallery, International School of Art, Umbria, Italy. Li’s work has been reviewed in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Art Forum, Art in America, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The New York Sun, New York Press, Cover, Artcricital.com, Abstract Art on Line, Painter’s Table, Hyperallergic.com and Morbihan France.

Kayla Mohammadi

Kayla Mohammadi is first generation American, born to a Finnish mother and Iranian father in San Francisco, California. Awards include: American Academy of Arts and Letters Purchase Prize in 2014; The Joan Mitchell Foundation Award for Painters in 2008 and The Joan Mitchell Artist Residency in New Orleans; The Dedalus Foundation Award for The Vermont Studio School Fellowship in 2008; Ludwig Vogelstein Foundation Grant in 2006; Blanche E. Colman Award in 2004; Constantin Alajalov Scholarship; and Vermont Studio School Fellowship in 2001. She has served as a juror for the Boston Young Contemporary Exhibition, the Rhode Island Council for the Arts Award in 2009, and Harvard University's Reflection in Action Judging. She is currently a Fine Arts Lecturer at Massachusetts College of Art in Boston. And has also taught at Brandeis University in Waltham, MA; St. Mary's College in Maryland; UMass Boston; Northeastern University in Boston; and the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University. She received her BFA from University of Washington in Seattle, and MFA from Boston University. She lives and works in Boston, MA and South Bristol, Maine.

Deirdre Murphy

Deirdre Murphy has exhibited internationally and extensively in the United States in museums, galleries and institutions including Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, Delaware, Minnesota, Washington and Oregon. Her work has been exhibited at institutions including the Philadelphia International Airport, Palm Springs Museum of Art, Biggs Museum of American Art, New Bedford Art Museum, Tacoma Art Museum, University of Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. The recipient of numerous awards and grants, most notably a Percent for the Arts sculpture commission (Dublin, CA) the Pennsylvania Council for the Arts Fellowship and a Leeway Foundation award, she has been an artist-in-residence at Lacawac Field Station (PA), Powdermill Nature Reserve (PA), Hawk Mountain Sanctuary (PA), Vermont Studio Center (VT) and Pouch Cove Artist Residency (St. Johns, Newfoundland). Her work has been published in Symbiosis, New American Paintings and Fresh Paint Magazine. Murphy’s work can be found in various public and private collections including Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Museum, Temple University, AlphaMed Press and Gamblin Artists Colors. Deirdre Murphy earned her MFA degree from the University of Pennsylvania and her BFA degree from the Kansas City Art Institute. Murphy is an adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania and been a visiting artist at Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania College of Design and University of Texas, Philadelphia University, Kent State University & Dickenson College. Deirdre Murphy is represented by the Gross McCleaf Gallery (Philadelphia), Boxheart Gallery (Pittsburgh) and Zinc Contemporary Gallery (Seattle).

Carrie Patterson

Carrie Patterson is a visual artist working in Leonardtown, Maryland. Her artwork considers how color, form, and line metaphorically measure the human condition as experienced through the body. She earned a B.F.A in studio art from James Madison University and an M.F.A in painting from The University of Pennsylvania. Additionally, she was a student resident at The New York Studio School where she worked with second generation abstract expressionists: Charles Cajori, Mercedes Matters, and Rosemarie Beck. Her artwork has been exhibited across the country with solo shows in New York City, Philadelphia, Virginia, and Minnesota. In 2017, her solo show titled Lightbox consisted of brightly colored cardboard constructions and stacked floor paintings at Hood Gallery at Mary Baldwin University in Staunton, Virginia. Recently, she has been making painted constructions based off her lived experience of architectural forms and their relationship to the landscape. She is a Professor of Art at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and former owner of Yellow Door Art Studios, a community art school. Her art curriculum called The Yellow Line features lesson plans for early childhood and K-12. Currently she is developing a course titled "How to See" for The Great Courses.

Rebecca Rutstein

Philadelphia-based artist Rebecca Rutstein – whose work spans painting, installation, sculpture and public art – explores abstraction inspired by science, data and maps. With interests in geology, microbiology and marine science, Rutstein has been an artist in residence in Iceland, Hawaii, the Canadian Rockies and Vermont. Most recently she has collaborated with scientists on board research vessels sailing from the Galápagos Islands to California, Vietnam to Guam, and in Tahiti, working with sonar mapping data of the ocean floor and shedding light on a world hidden from view. Rutstein is slated to make her first descents in the deep sea submersible Alvin off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica in October 2018 with a science team from Temple University, and off Mexico’s Gulf of California in November, 2018, with a science team from University of Georgia, where she will also be a visiting fellow. With over 25 solo exhibitions, Rutstein has exhibited widely in museums, institutions and galleries including solo exhibitions at the California Museum of Art Thousand Oaks, Exploratorium (CA), Cornell University (NY), Philadelphia International Airport, Swarthmore College (PA) and Fleisher Art Memorial (PA), and in group exhibitions at the NY Hall of Science, Susquehanna Art Museum (PA), Bishop Museum (HI), Bucknell (PA), Rowan (NJ) and Virginia Commonwealth Universities. She has received numerous awards including a Pew Fellowship in the Arts, an Independence Foundation Fellowship and a Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Grant. Rutstein has garnered recent attention through interviews and features on NPR, Huffington Post and Vice Magazine. Her work can be found in museum and public collections including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Museum, Temple University, Johns Hopkins Hospital & Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Rutstein holds a BFA from Cornell University (with abroad study in Rome) and an MFA from University of Pennsylvania. She has been a visiting artist at museums and universities across the US and enjoys speaking about the intersection of art and science. Rutstein is currently represented by Bridgette Mayer Gallery (Philadelphia), Zane Bennett Contemporary/Form & Concept (Santa Fe) and Sherry Leedy Contemporary (Kansas City, MO).

Kendra Wadsworth

Kendra Dawn Wadsworth graduated with honors from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1996, earning a BFA in Painting and Printmaking. She went on to further her education at the University of Pennsylvania where she received her MFA in Painting in 1998. Wadsworth’s paintings have been featured in solo and group shows throughout the country. She has received numerous awards acknowledging her artistic achievements, recently being awarded with a 2010 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Professional Fellowship. As a result of this accomplishment, her work was installed at the VMFA for six months. Professionally, Wadsworth has executed her knowledge and skills as a Painting and Drawing Instructor. Currently, she is on faculty at Virginia Commonwealth University, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the Visual Art Center of Richmond. In addition to her teaching skills, she has worked as a Union Scenic Artist local 829 for a number of theatrical and major motion pictures in NYC and Philadelphia, PA, most notably designing and executing all of the installation art work for the Academy Award winning film, A Beautiful Mind.